Myanmar Is A Travel Photographer’s Dream

Until quite recently Myanmar was a difficult country to visit. The country was ruled for many decades by a military junta that was deeply suspicious of foreigners and that sought to keep international businesses out of the country. The paranoid isolationism of the governing generals stunted economic and social progress and kept Myanmar poor and under developed. Tourism was not encouraged. It took some effort to get a visa to visit there.

So suspicious of outsiders was the military government that it refused admittance to international aid groups for a whole month after Cyclone Nargis swept through the Irrawaddy Delta in 2008 and killed an estimated 130,000 people outright. The government’s hesitance to accept outside help for survivors of the cyclone cost hundreds of thousands of more deaths from starvation, disease, and dehydration.

With democratic elections in 2015 that saw Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi leading a new civilian government, Myanmar’s days of self imposed solitude seem to be coming to an end. Tourist visas are considerably easier to get now and foreign visitors, eager to get there before an inevitable tidal wave of touristic commercialism descends on Myanmar, are streaming into the country.

That Myanmar is currently undergoing development at a breakneck pace was quite obvious to me when I was there. Without exception, in every part of the country I visited I saw evidence of such development. Hotels were under construction, roads were being improved, Yangon’s airport was being expanded, and various commercial properties were being built.

So far at least the dominating influence of international corporate brands in Myanmar is still in its infancy. I saw a single KFC restaurant in central Yangon, the country’s largest city but that was the only time I noticed any Western fast food restaurants. To date, cars and cell phones seem to be the leading pioneers of Western consumer culture present in the country.

Despite the Generals willingness to allow Myanmar to begin transitioning into a more open society, they still retain a great deal of power. A quarter of all the seats in parliament were reserved for politicians linked to the former military regime and the so-called “Cronies”, wealthy people and families with close ties to the military brass, still control a disproportionate amount of the country’s businesses and wealth. Myanmar’s military establishment is not used to civilian oversight. Whether the military will ever truly cooperate with a freely elected government in the future will be the main determining factor affecting the viability of democracy in Myanmar.

Myanmar has an incredibly diverse ethnic composition. More than 120 different ethnic groups speaking about a hundred different languages live there. Some of these ethnic groups feel no attachment to Myanmar and its majority Bamar people. Low level wars for independence from Myanmar still occur in peripheral areas of the country. For that reason, tourists are still prevented from traveling in large tracts of the country.

For decades the only interest the central government had in its more remote territories of Myanmar was in exploiting their natural resources. Forests rich with teak trees and other valuable tropical hardwoods have drawn the attention of those wishing to profit from them. Myanmar has abundant deposits of jade and rubies to tantalize the dreams of covetous Crony business people. The best way to exploit those riches would be to first remove the people that live where they’re located. Needless to say, that logic has met with fierce resistance within the hinterlands of the country.

Due to the ban on travel to regions of the country where tribal groups occasionally clash with the military, visitors don’t get exposed to that turmoil. Most of the country can be explored by foreigners and it’s a peaceful and often thrilling experience. Myanmar encompasses a wide array of natural habitats and geographic features. The ancient sites of Mrauk U and Bagan are stunning in their beauty and scope. Were it not for Myanmar’s long years of seclusion Bagan and Mrauk U would be famous in the West instead of being obscure.

Food in Myanmar was a real treat. The variety of dishes along with the huge assortment of spices and herbs ensured that my palate would never suffer from boredom. In addition to native Burmese cooking, which was always delectable, there were almost always Chinese, Indian, and Thai dishes available for enjoying also. Food was everywhere. Along with fresh produce, fish, and meats, markets usually had food stalls where I could get a tasty, filling meal prepared in front of me. The same was true for the many food carts and stalls on the streets of some places. I really wanted to try fermented tea leaf salad, a traditional Burmese dish. That sounds gross but it is apparently delicious. Unfortunately, I never saw it served in any place I ate.

Most hotels offered a complimentary breakfast. I usually succumbed to the convenience that offered but generally speaking, those meals were usually uninspiring. In most cases I should have gone hunting for Mohinga, Myanmar’s national breakfast.

I was very pleased with the flavour of the beer made in Myanmar. The most common brand was appropriately named for the country itself. Myanmar beer was a full-bodied lager and absolutely delectable. It tasted like it was made from only barley malt with no adjuncts used. Mandalay brand beer was a paler and weaker tasting lager but not bad by any means. I’ve long been a lover of good stouts and Myanmar brews two delicious brands. ABC Stout is rich and sweet and Black Shield Stout is dry with a fabulous taste of espresso coffee and dry dark chocolate. Both of those stouts pack a hefty alcohol content.

Rum is also made in Myanmar. It’s quality was poor (at least among the few I tried). It was obvious that artificial flavourings had been added to the rums I sampled there.

People in Myanmar were very friendly to me. It was quite common for passing strangers to smile at me and say hello. Both men and women did that. Frequently I was stopped on the street by men who were simply curious about me. They wanted to know where I was from and what my impressions of Myanmar were. Never did that lead to anything untoward. None of those brief conversations led to attempts to scam me or to convince me to buy anything as is so often the case in some countries. In fact there seemed to be almost a complete lack of hustlers on the streets. I encountered a few in Yangon but a simple “No thanks” in passing ended the conversation with no further ado.

Yangon

My introduction to Myanmar was the international airport in Yangon (formerly called Rangoon). It was a modern facility and getting through customs was a breeze.

I had booked a hotel online for my first few nights. It was more expensive than what I had been accustomed to paying in other South East Asian countries but that was a peculiarity of travel in Myanmar. Most things were predictably inexpensive but hotel rooms, while still a bargain by Western standards, cost more than you would expect if you’ve been to that region of the world before. Anyway, one should judge a destination for how much it offers, not how expensive it is.

My hotel was very central and just off the eastern edge of Yangon’s Chinatown. I wanted to be able to walk to most sights in the city and be close to a wide choice of restaurants. I wasn’t disappointed there. Chinatown offered a great selection of good restaurants and places to grab a drink. One street in particular, 19th Street, had outdoor seating that was always packed at night with travelers and locals alike. It was often difficult to find a seat but once I did I would find myself sharing a table, and possibly conversation, with others.

Yangon was very hot and for some reason the humidity seemed much worse at night. I would invariably find myself sheathed in a thin layer of sweat as I sat in the muggy miasma of Chinatown during evenings on 19th Street. Looking around at others I had to conclude that I was more affected that way than most people.

There’s no getting away from the fact that Yangon is a filthy city. Trash, some of it emitting very rank odours, was ever present. Other cities I had been to in South East Asia were notably cleaner. Additionally I was shocked at the number of rats in Yangon. Especially at night, rats were scurrying around and darting in and out of holes in the sidewalks and roads in significant numbers. Not since I had been in India nearly 30 years before had I seen so many of my least favourite animals.

Shwedagon Paya is Yangon’s leading attraction. Paya is the Burmese word for temple. Shwedagon Paya is more than just a temple though. It is Myanmar’s premier Buddhist holy site and one of the most impressive in the whole of Asia. I’ve seen my share of Buddhist temples. None impressed me more than Shwedagon. The central stupa is 99 meters in height and it dominates the skyline of Yangon especially at night when it’s lit up with spot lights. This massive stupa is gilded with real gold; more than 20,000 gold bars worth! The grounds surrounding the main stupa are carpeted with smaller shrines and pavilions with pointy metal roofs poking heavenwards. The whole complex glimmers under the tropical sun. Buddhist monks wearing orange robes and nuns garbed in pink ones roam the site, their bald heads gleaming. There are Buddha statues everywhere you turn but one of the most impressive of all is one made of 324 kg of solid jade. The whole complex was truly astonishing to see but there was so much to take in that my eyes didn’t always know where to focus.

It’s never any problem for foreign non-Buddhists to enter Buddhist temples in Myanmar so long as they remove any footwear (including socks) before entering. That’s a custom adhered to in all Buddhist countries I’ve traveled in. I do remember being able to keep my socks on in Thai temples though.

On leaving Shwedagon Paya I caught a cab to Chauk Htat Gyi Pagoda the site of a giant reclining Buddha statue. The statue is 66 meters in length officially making it the biggest reclining Buddha I’ve ever set eyes on. The face of the statue was extremely effeminate to an extant that couldn’t have been unintended. The Buddha was depicted with blue eye-shadow and extra long eyelashes. More interesting were the hieroglyphs on the soles of the feet of the statue. I had not seen that featured on other reclining Buddhas.

Bogyoke Market on the northern border of Chinatown was a great place to browse and shop for Burmese crafts. Many of the shops in the market cater mostly to tourists but there are plenty that service the needs of local people. My first attempt at going to Bogyoke was on a Sunday and it was closed. That was just as well. It made more sense for me to return there when my trip was coming to an end rather than when it was just beginning. I did in fact return to the market on my last full day in Myanmar. I wandered through the shops for hours and really enjoyed it. I love looking at antiques, paintings, and handicrafts and plenty of those were on display.

After making a few purchases at Bogyoke, I sat at an outdoor table at a coffee shop immediately east of the market. Myanmar is a tea growing and tea drinking country. Getting a decent cup of coffee in Myanmar is a real challenge. Usually when you order coffee you’re served instant Nescafe. Even worse, sometimes you’ll receive a packaged mixture consisting of instant coffee, powdered milk, and a sickly sweet dose of sugar. When I spied what looked like a genuine coffee shop I was excited. I began reviewing my newest photos on my cameras memory card as I sat and waited to be served. Soon I noticed a small sign on the table top stating that customers needed to go inside and place their orders at the counter. That’s just what I did. After returning to my table I saw that I had left my camera sitting there. I almost had a fit. I couldn’t believe that I could be so forgetful. The street was alive with people. How many dozens of people had walked past within easy reach of my (not inexpensive) camera? Throughout my travels in Myanmar I had felt absolutely safe and was impressed with the honesty and integrity of its people. Leaving my camera unattended for at least 5 minutes and in plain sight on a busy thoroughfare and being able to return to find it where I placed it seemed to me the ultimate test of the decency of people in Myanmar, one of Asia’s poorest countries.

Just a block south of Bogyoke Market is Theingyi Zei Market. That provided me with my first close-up view of a real Burmese market. Theingyi is fascinating to walk about in and observe a slice of life as Burmese people experience it. It’s crowded, clogged with boxes, stalls, garbage, bicycles, meat that never sees the inside of a refrigerator, and shoppers all crushed together in one spot. It’s a market designed only with the needs of local people in mind. There are no antiques, souvenirs, or handicrafts to be seen.

Sittwe

Sittwe is a small city in northwest Myanmar on the shore of the Bay of Bengal. I decided to buy a plane ticket from Yangon to Sittwe rather than endure an arduous 2 day bus trip. It’s not too expensive to fly within Myanmar and it sure saves time getting from place to place. On arrival at Sittwe’s tiny airport I and the rest of the passengers had to go through a police passport check before being allowed to exit the airport. I was to discover, later after booking a couple more flights, that that is routine procedure. That was the only real reminder of Myanmar’s continuing police state presence that I was confronted with in my 3 weeks in the country.

I was surprised to see a sign at the airport that offered applications for permits to visit the Rohingya refugee camps near Sittwe. The Rohingya are Muslim that have resided in Myanmar for generations but are denied citizenship by the central government. According to the government the Rohingya born in Myanmar are actually citizens of Bangladesh. Bangladesh does not want to provide refuge to them however. Effectively that leaves the Rohingya stateless. Tensions between the Rohingya and the Buddhist majority have been a fact of life in northwest Myanmar for generations. In 2012 anti Rohingya riots broke out throughout Rakhine State (where Sittwe is located) leaving dozens, and possibly hundreds, of Rohingya dead.

I saw the burned out hulk of a mosque on the main street of Sittwe. It was fenced off from the road with a slapdash wooden barricade. That was a stark reminder of the fact that the Rohingya have been pushed out of Sittwe. Now they languish in camps outside town, banned from returning to their homes and businesses.

In the West we tend to think of Buddhists as being always peaceful. That’s at least due in part to the public persona of the Dalai Lama. In Myanmar the Buddhist clergy has been instrumental in whipping up anti-Rohingya sentiment and in condemning aid groups that assist them. So popular is hatred toward the Rohingya that Aung San Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s answer to Nelson Mandela, refused to condemn the persecution directed at them.

I knew that applying for a permit to visit the Rohingya camps would take time that I couldn’t afford. In a country that is careful to only expose it’s untroubled side I couldn’t help wonder if visits to the camps by tourists would be carefully stage managed and thus not worthwhile. The recent easing up of restrictive military rule has done nothing to help the Rohingyas and with even liberal, democratically-minded Burmese unwilling to take up their cause it’s hard to believe that much will done to help them in the near future.

When the British ruled Burma they amalgamated it with India. Many people from India moved to Burma during those years and their descendants live there today. I saw many people in Sittwe who were clearly of Indian ancestry. I couldn’t help wonder why they weren’t discriminated against like the Rohingya. Perhaps they were part of the Buddhist majority.

Sittwe is best known among travelers as the best staging point for visiting Mrauk U, the monument-studded medieval capitol of the former Kingdom of Arakan. Accordingly most visitors just pass through on their way to Mrauk U.

I had read that the market in Sittwe was one of the most captivating in the country to visit and photograph. That was enough to convince me to spend a couple of days there.

The market in Sittwe is located on the very edge of the Bay of Bengal. There is a jetty immediately next door where the town’s fishing fleet is moored. The market is strategically placed to receive the fishing fleet’s catch as it is brought to shore, ensuring a fresh daily supply of fish. It was enthralling to watch fishermen row their boats out to sea to fish early in the morning. Later in the day as the boats returned teenage boys were employed to bring large heavy buckets of fish into the market. It was dirty, strenuous work.

I went to the market for 2 consecutive mornings and stayed for much of the day. I could count the number of other tourists with the fingers of one hand. I felt almost like I had the place to myself. Being mostly a fish market where none of the fish ever got iced or refrigerated, it was not pleasant smelling there upon first arriving but I soon got used to the fishy funk in the air.

I was able to wander freely and take whatever photos I wanted. I was beginning to discover that people in Myanmar are very tolerant of the idea of being photographed by foreign visitors. In the many hours I spent taking photos at the market no one tried to avoid having their picture taken or displayed any concerns about me doing so. I would find that that attitude prevailed everywhere I went in the country. Much to my delight I could snap away with complete abandon. As a result I managed to accumulate more portrait photos in Myanmar than any other destination I’ve traveled to .

Close to my hotel was a cluster of trees that acted as a home base for a large colony of fruit bats. They would hang upside down from the tree branches during the day looking like big, elongated black fruit. At dusk they’d come to life and take flight. Hundreds of bats, resembling flying terriers made for an awesome, and slightly disquieting sight, even with the knowledge that they were harmless.

Aside from its fascinating market Sittwe’s attractions are thin on the ground. I checked out the Rakhine State Cultural Museum. My guidebook said it was good for an hour’s worth of distraction. That assessment was much too kind.

My guidebook also mentioned the Bhaddanta Wannita Museum and described its exhibits as underwhelming. However it also said that resident monks enjoyed practicing their English with foreign guests. That sounded appealing to me so I decided to go there. That took longer than I expected since no one I asked seemed to know where the place was. In fact it was so easy to miss that I had walked past it while searching for it. The guidebook was right about the lifeless exhibits in their dusty glass cases. Unfortunately no monks approached eager to to converse with me. A couple of them were sitting down to a meal when I arrived but they paid me no attention. Maybe curious foreigners had become too routine to bother with.

To catch the ferry from Sittwe to Mrauk U I had to rise before dawn. I had made prior arrangements for a motorcycle rider to zoom me out to the ferry dock. For an extra dollar I got to sit on a bench on board for the duration of the trip. The only other people doing that were fellow Western travelers. All the local people who were passengers on the boat sat on the hard steel deck. There was one white guy that spent the whole half-day journey sleeping on that deck. Maybe he was sick or monstrously hungover. I don’t have any recollection of seeing him outside of his sleeping bag once he got settled in.

Mrauk U and the Chin Villages

Mrauk U was one place I was excited to see. After reading about it online and in my guidebook I was enthusiastic to see the centuries-old stone temples scattered around the outskirts of the town. My first view of Mrauk U was not the least awe-inspiring however. Arriving by boat I saw nothing more than a few ramshackle wooden buildings and a very dusty dirt road leading away from the river bank. In truth the town itself is just a typical rural Burmese backwater. No doubt that will soon change as the onslaught of international tourism ramps up in Myanmar. For now it’s hard to believe that Mrauk U was once the capitol of an empire that existed for three and a half centuries and encompassed much of present day Myanmar and Bangladesh. Mrauk U was sacked in 1784 and has not mattered politically since then.

Mrauk U is actually pronounced like “Meow OO”. The English spellings of Burmese place names can be very odd. Another city I visited later in my trip was Kyaukme which is pronounced “Chowmay”. Likewise, Kengtung, also a place I went to later, is pronounced as “Chengdong”. I don’t know how any one could have arrived at the decision to create such a disparity in spelling and pronunciation of names such as those.

Mrauk U is quite small and its easy to walk to many of the of the temples. Many visitors rent bicycles to tour around. I didn’t see a single tour bus in the 3 days I was in Mrauk U. How long will that last?

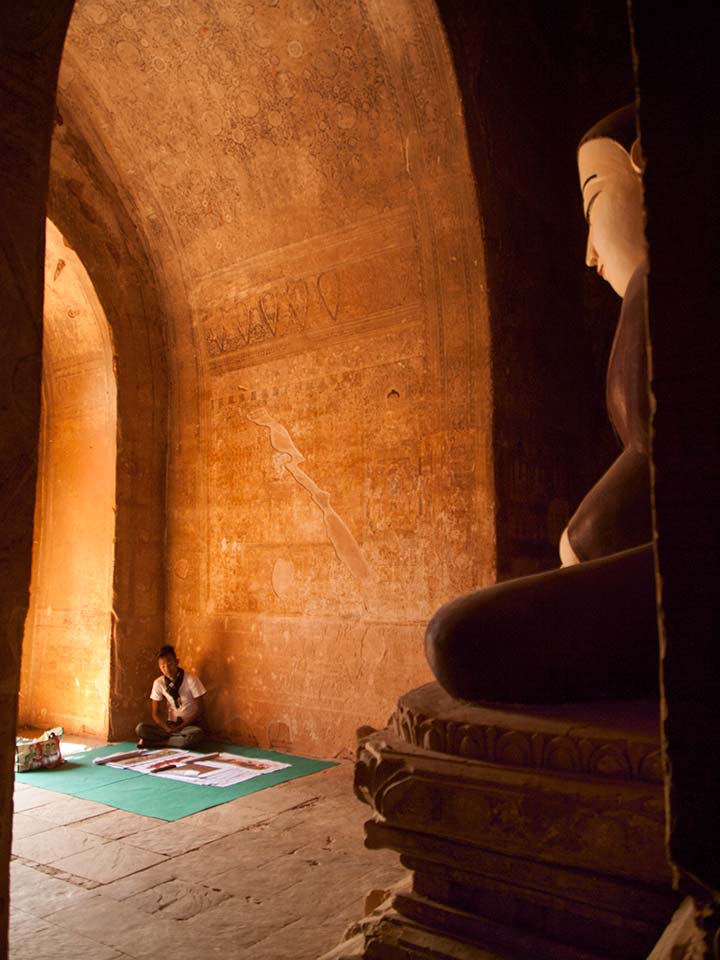

The temples are not delicate looking edifices. In some cases they are so solidly constructed that they resemble fortresses more than places of worship. The design and layout of each temple is unique which encouraged me to try to visit as many as I could.

Tourism in Mrauk U is still undeveloped enough that I always found myself alone at each temple when I visited. I was tempted to not take off my shoes and socks when I entered them. There were countless little pebbles and bits of grit from the temple bricks underfoot. I have flat feet and wear custom arch supports. I’m not accustomed to going barefoot so the soles of my feet are baby-bum soft. I resisted the the temptation to not remove my footwear though. The Burmese had treated me hospitably and I saw no reason to possibly risk offending any that might happen by. I hobbled around the temples like I was walking through hot coals.

Exploring the temples around Mrauk U is reason enough to go there. There is another compelling reason to visit the place. Not too far away are villages inhabited by tribal people called the Chin. The Chin people had a custom of tattooing the faces of their women with dark blue ink. It is said that they started doing this to make their women less sexually appealing to men from outside the tribe. Whether that was really the case, the tattooing has long been outlawed. Today the youngest Chin women with tattooed faces are in their late 50’s. I was intrigued with the idea of visiting some tribal villages and getting a glimpse of a way of life I was completely unfamiliar with.

According to my guidebook my best bet for arranging a visit to the Chin villages was to hook up with a local man nicknamed Mr. Fix-It (real name, Aung Zang) who reportedly usually hung out in front of one of the budget hotels in town. As luck would have it, the first person I approached at that hotel was the man himself in the flesh. Aung had a moon-shaped face and a ready smile. I liked him right away and felt confident handing over the cash to pay in advance for the journey and his services as a guide and translator. He charged a flat fee regardless of whether there was one ,or up to four people, to shepherd out to the villages. I hadn’t made friends with any fellow travelers in town so I had to pay the full amount just for myself. I didn’t mind. I hadn’t ventured that far to cheap out on a unique opportunity.

True to his word, Aung met me bright and early the next morning out in front of my hotel and we set out in a motorcycle-powered taxi for the Lemro River. Most of the distance from Mrauk U to the Chin villages was traversed by a motorized canoe. It took a few hours to reach our destination. It was a relaxing trip upriver through forested countryside.

When we got to the first Chin village we scrambled up a dirt embankment for about a minute before reaching level ground. Aung was soon surrounded by Chin children. They recognized him and knew he was carrying candy to give to them.

I could see some huts made of bamboo and palm fronds. Along with lots of small children, pigs and chickens wandering about pecking or snuffling around for food. I was definitely in the sticks, no doubt about that. I couldn’t help notice that some of the huts had solar panels on the ground next to them. Electrical cords ran from the solar panels and into the huts. I had to wonder what the solar panels were powering. I couldn’t hear the sounds of any electric or electronic gadgetry or the drone of TVs or radios. I soon forgot about the solar panels and never asked Aung what their purpose was.

There were no other foreigners in any of the 4 villages Aung led me to. While it was clear from the reactions of the people in the villages to my presence that they were habituated to the concept of foreigners dropping by to gawk and take photos, they didn’t seem to have reached a point of getting weary of that. Without exception they were friendly to me but also a little shy. So I was a little taken aback when one of the tattooed Chin woman put her arm around my shoulder and told Aung that she wanted him to take a photo of me and her together.

In the last of the Chin villages we visited the women with tattooed faces were selling colourful scarves that they had woven themselves. I bought some of the scarves despite not having a use for them. I didn’t face any pressure to buy but I wanted to help them out a bit.

Some argue that visiting tribal people in order to add to your photo collection is voyeuristic. I disagree entirely. To begin with voyeurism implies spying on the private actions of another person without their knowledge or consent. I didn’t feel like a Peeping Tom when I photographed people in the Chin villages. They were very much aware of my presence and gave permission for me to take their picture. I don’t understand what could be exploitive or selfish about that. When people of disparate culture come together peacefully, no matter how briefly, it mutually expands on their realization of our shared humanity.

Bagan

Bagan is without doubt the number one tourist attraction in Myanmar. Bagan lies in the flat central plain of Myanmar and is home to literally thousands of temples, shrines, and pagodas. It’s not easy to find the right words to convey the grandeur and immensity of the site. The best way to try to take in the whole spectacle is to pay hundreds of dollars to be taken high up enough in a hot-air balloon to get a panoramic view. I’m too poor (and cheap) to have done that. I satisfied myself by getting around on foot or by hired horse carriage for longer distances.

Bagan was the capitol of the Kingdom of Pagan from the 9th to the 13th century. It was that kingdom that would eventually form the nucleus of what would eventually evolve into the current day state of Myanmar. Over the centuries many different architectural styles, with influences inspired by other Asian cultures, were used to build the temples of Bagan. At its height Bagan was an important center for religious and secular studies and attracted acolytes from India, Sri Lanka, and the Khmer Empire (in present day Cambodia).

Bagan consists of 3 parts. Old Bagan, the original settlement, is surrounded by a stone wall which encompasses many of the finest temples in the area. The Burmese government moved the inhabitants of Old Bagan into New Bagan to the south. Such is the power of the Burmese government.

The third portion of Bagan is the small town of Nyaung U. It’s there that most of the budget hotels and restaurants are to found. Nyaung U also plays host to Shwezigon Pagoda which rather resembles a smaller version of Yangon’s Shwedigon Paya. Shwezigon seemed way to0 large a complex to be located in such a small place as Nyaung U. It was impressive not only in size but in gilded pomp as well. It appears younger than it is but is nearly 1,000 years in age.

I took my guidebook’s advice and started my exploring of the temples of Bagan in Old Bagan. I rented a horse carriage and driver in Nyaung U and we trotted the few kilometers to Old Bagan. Once we arrived at the Tharaba Gate on the city wall I headed off walking toward the temples. While there were other tourists off in the distant whenever I visited one of the temples, I always had each one of them to myself. It was possible to visit most of the temples in a circuitous route without the need of doubling back to any previous point I visited. It took several hours to accomplish that. I was wearing short pants and managed to get my legs all scratched up by shrubs, thorns, and bushes laying between the sites. There was often no path to follow so I had to make my way from one temple to another by wending my way through underbrush in some cases.

Next day I visited the crafts market in Nyaung U. It was a great place to pick up some locally made souvenirs. Lacquerware is a local specialty and some of it was distinctive and made with accomplished skill. So I bought some.

It was in the crafts market in Nyaung U that I had my one and only confrontation with an aggressive sales pitch during my stay in Myanmar. After I purchased a carved wooden head of a Burmese girl from one merchant, a merchant from an adjoining stall began following me around the market with a similar item from his stock. I told him repeatedly that I wasn’t interested in buying what he was offering. Nevertheless he continued to implore me to pay him for the item. Time and again he attempted to hand the carving to me as though me touching it would somehow seal the deal. As I went from stall to stall he persisted with his pitch. I had been in Myanmar long enough to not expect that level of harassment. But I had been in countries where it was routine to be subjected to that sort of barrage of pestering ( I’m thinking of you India, Egypt, and Morocco). I wanted to prove to myself that I had become worldly enough to wear down that type of noxious pest without losing my cool. I started to walk through the market with him following close on my heels. Soon he reached a point of practically begging me to buy what he was proffering. I stopped telling him I wasn’t interested and ignored him instead.

In Asia it is really bad form to make a spectacle of yourself in public and my pursuer was doing that most egregiously. I could see that the other merchants were refusing to lend him support. They shunned him by avoiding eye contact with him. Whenever we approached a stall the people behind the counter cast their eyes downward so they wouldn’t have to look at him. They were clearly embarrassed by his behaviour. After what seemed like a much longer period of time that I’m sure it was, he finally gave up and silently sulked back to his shop. I had had too many pleasant interactions with other people in Myanmar to let one bothersome encounter colour my view of the country.

On my last full day in Bagan I rented another horse cart and driver to take me to see some very splendid old temples outside the small village Minnanthu. Once again there were some other tourists around those places but they were few in number. I got some curious looks from some local women selling cold drinks outside one of the temples. They were looking at my legs and were obviously curious about the cause of the lacerations.

Mandalay

I left Bagan before dawn to take a ferry down the Irrawaddy River to Mandalay. That was the slowest option for getting there but I hoped to see some picturesque scenery on the way. In fact, the central plain of Myanmar is flat and rather featureless. I did get to witness dawn over the Irrawaddy which, though not breathtaking, was vivid with pinks and oranges and pleasing to see.

For me the name Mandalay conjured up images of ancient palaces and temples all set in a fantastical tropical setting with an abundance of elephants, monkeys, and peacocks traipsing around. It was a place with a name that said “exotic” to me. I was surprised to discover that Mandalay was not founded until the middle of the 19th century. There was a royal palace there but it was flattened by bombs in World War II. A replica was put up in the 1990’s but after coming from Mrauk U and Bagan I wasn’t about to be bothered with going to see a modern fake.

Mandalay is Myanmar’s second largest city but worthwhile sites are in scant supply. I did enjoy going to see Shwe In Bin Kyaung a wooden Buddhist temple with very pleasing wooden carvings on its walls. There are also some extremely colourful Hindu temples in the Hindu district.

There’s no lack of good places to eat in Mandalay. I love Indian food and looked forward to trying an Indian restaurant recommended in my guidebook. When I got there the place was hopping. I managed to find a small empty table that hadn’t been cleared of the residue from the last diners to sit there. I sat and waited and waited some more. The waiters were making a conscience effort to avoid eye contact with me. I understood they were busy and probably weren’t looking forward to more work (ie. another customer to have to deal with).

Most of the other travelers I had met in Myanmar were French or German. In both of those countries tips for the wait staff are automatically added to the dinner tab. As a result, French and German tourists don’t usually stop to consider how much to leave their server for a gratuity. Instead they pay the total asked for and keep the change. It was obvious to me that no waiter at this restaurant viewed me as a possible source of a few extra kyat ( the name of Burmese money, pronounced “chat”, yet another odd phonetic rendering of Burmese to English). I considered getting up and leaving just as a waiter stopped by with a menu. He didn’t take the trouble to wipe the table but I had long become acclimatized to the standard of service in Third World countries and thought nothing of it.

After settling on the Chicken Curry as my choice for a meal I waited for a several long minutes until again reaching the point of thinking I should just get up and walk out. Just before I did a different waiter showed up to take my order. Although he was in his early 20’s he had the demeanor of someone who’s seen it all and was weary enough to just want to get the transaction done as quickly as possible. I told him my order and with his apathetic, world-weary look he turned heel and disappeared, again leaving the table obviously still dirty.

Yet again I waited longer than I though necessary for my food to arrive. Yet again I was thinking I should go somewhere else and just before I acted on that impulse my food arrived. By that point I was weak-in -the-knees hungry. I ravenously tucked into my meal only to discover that it was cold. I looked around for someone on the wait staff to appeal to only to observe the same lack of interest in helping me that had defined my experience since my arrival.

My first though upon sampling my dinner was that I could get seriously by sick eating it. Ensuring that your food is fresh and hot is the best way to avoid getting food poisoning when traveling in a poor country. My second thought was that I had eaten food in places that looked a lot more dubious than the one in I was currently in without getting sick and had done so for nearly 30 years. I went with my second thought.

After paying my bill I grabbed a takeout beer and a 1.5 litre bottle of water from a store, returned to my hotel and watched a really bad action movie piped in on cable TV from India before turning in for the night.

Just before dawn I awoke with a massive gut ache and the urge to run to the toilet. I made it to the bowl without a millisecond to spare. Now I’m not about to provide any details of my gut condition except to note that it was most unpleasant to the senses on all levels of how we commonly understand such things. I was completely drained of vigour. I had to expend far more energy than usual just to make it back to bed. That was my routine for the next several hours. Sleep, wake up suddenly when the potty training inculcated so many years previous kicked in, and then struggle to remain on two feet long enough to make it back into the now sweat-soaked bed.

When I was out of the bed my movements were uncoordinated and I worried about losing my balance and falling to the floor.

At one point my slumber was interrupted by some knocking on the door of my room. In my condition I just wanted to ignore that hindrance to my rest. I looked at my wristwatch. It was past one o’clock in the afternoon. I hadn’t paid for another night in the hotel. The knocking continued and I could hear women’s voices speaking what I presumed was Bamar. I imagined that the hotel management was on the other side of the door wondering why I had overstayed past checkout time. I really didn’t want to get out of bed. Despite having slept several hours uninterrupted I was exhausted. My gastrointestinal system felt like it was stuffed with hot coals. I had aching flu-like symptoms over my whole body. I yelled through the door that I would go downstairs and pay for another night. Soon.

The knocking continued. There was no way out. I had to answer the door.

After I unlocked the door and opened it I saw 2 very tiny Burmese cleaning ladies standing in the hall with an abundance of cleaning supplies and fresh linen and towels in tow. They looked rather surprised to see me. Then again my hair was disheveled and my eyes were watery and bloodshot. The fact that I was wearing only undershorts and sporting more body hair than a dozen Burmese men would be hard-pressed to come up with together may have played some small role in startling them. They quickly composed themselves and asked “Want room clean?”. I declined their offer.

So the management wasn’t yet gunning for me, I thought. The temptation to flop back onto the bed was powerful indeed. But I wasn’t delirious enough to think that I could stay in the room indefinitely without paying for it. It took some effort to get dressed. I washed my face and combed my hair. I still looked like crap but there was no helping that.

I was on the 4th floor of a cheapie hotel. The lobby of course was on the ground floor. I was unsteady on my feet and had to make generous use of the handrail on the stairs going to the lobby. I paid for 2 additional nights.I wasn’t sure how long I would be out of commission. Nobody asked why I was late paying. I wasn’t charged any sort of penalty for doing so either.

If going down the stairs took effort, going back up was a nightmare. I felt like my body weight had quintupled. My joints groaned as I very slowly climbed the stairs back to my floor. I think I know what being 90 feels like now.

I slept most of the day. I didn’t leave my room at all until the next morning. I had had nothing to eat for the duration, not that I craved any. Luckily I was well stocked with bottled water.

The next morning I felt much better. By then I had successfully expelled all the toxic waste that my curry dinner had provided me with. I actually had an appetite. That’s always a sure sign that the worst that food poisoning has to offer has passed. I had the complementary breakfast offered by the hotel and felt better still.

I was still feeling a little shaky but I didn’t want to miss out on another day of touring and taking photos. After going back upstairs to get ready for another excursion I exited the hotel. There were always some motorcycle taxi drivers hanging around outside with their respective steeds waiting to rocket some foreigner to where ever it was they wanted to go. I was interested in going to a small town not far from Mandalay called Paleik. My destination was Hmwe Pays, better known as the “Snake Temple”. Hmwe Paya plays host to some Burmese pythons that are allowed to live there by the resident monks. Everyday at 11 AM the pythons are lovingly bathed in a small tiled pool in water graced with flower petals. I wanted to see that.

Another amazing thing about Myanmar is the fact that even taxi drivers (almost invariably venal just about everywhere I’ve ever been) still quote fair rates to foreigners. I don’t recall how many kyat I laid out for my ride on the back of the motorcycle to Paleik but I paid the first quoted price because I believed it to be fair. The same was true for other taxis I took while in Myanmar. The inevitable tourist invasion in the near future will probably put the practice of drivers not demanding exorbitant fares to rest for good.

I arrived at the Snake Temple well before the time for the snake bath to get underway. I had plenty of time to wander around bare foot inside of the temple complex and take photos. When it came time for the big event a crowd gathered around the small square pool where the pythons were to be bathed. Burmese pythons can reach eye-popping lengths but the ones the monks brought out were only about 2 meters long. The actual bath was anti-climatic. The pythons were surprisingly docile (at least to my thinking) and scarcely reacted to being placed into the pool. Well I suppose that’s just as well. Stressed out Burmese pythons are probably not a treat to deal with.

Despite the rather lacklustre main event I was really glad to have visited Hmwe Paya because I got some good people photos there. Then again, that largely defined my experience of Myanmar.

On the way to, and coming back from Paleik, we had passed a section of Mandalay where dozens of artisans were using power tools to craft Buddha statues of varying sizes in the open air. It appeared that these artisans were responsible for carving the features of the face and head of the statues since most of them were complete except for having square-shaped blocks of stone where their heads were supposed to be. All of the statues were of white stone. Whether it was marble or some sort of man-made stone composite, I couldn’t tell. All I knew for certain was that I definitely wanted to return there the next day to watch and photograph the artisans at work.

Next morning I looked for the same motorcycle driver to take me to where I had seen the outdoor Buddha statue workshop the previous day. He was nowhere in sight. I approached another driver and began asking about the whereabouts of the place where they add the finishing touches to white stone Buddha statues. He knew right away where that was. He then pulled out a laminated copy of different workshop tours with their respective prices from the storage space under his motorbike seat. I had the option of adding tours of gold leaf producing studios along with woodworking studios in addition to the tour of the place where the ghostly white Buddha statues were finished. I aked to be taken to all 3 workshop areas.

First up we went to a workshop where men were making the ultra thin gold leaf wafers that Buddhists smear on religious statuary. Essentially the gold is pounded flat and made so delicately thin by being repeatedly pounded with wooden mallets. It takes hundreds, if not thousands of blows of the mallet to achieve the finished product. It’s work that only young men could do since it involves such so much physical effort. Injuries from the repetitive hammering must be common. The workers swung the mallet from over their heads to ground level at a very fast pace. It was a hellish way to make a living.

In an adjoining room women and children were packaging up the small sheets of gold foil into small boxes in preparation for shipping. It’s very common to see child labour in practice in Myanmar.

Next the motorcycle driver zoomed me over to a woodworking shop where men were carving ornate wooden screens with traditional Burmese style designs. Each artisan worked kneeling over the panel being carved as it lay on the floor. There were an assortment of chisels of varying sizes beside each man. The finished products were on sale at the same location. There were very beautiful and very elaborate. I’m sure they must have been very expensive.

Lastly we went to the outdoor stone carving site I had seen in passing the previous day. Most of the artisans were of Indian ancestry and their dark faces were powdered white from the dust of the stone they were chipping, grinding, and sanding. They had no protective gear for their eyes and they were obviously breathing in the fine stone dust as they worked. It was appalling to see people working under such conditions. All of the workers were young. I couldn’t help wonder what the life expectancy of their career was. They completely ignored me as I walked among them. That allowed me to get several candid photos of them as they worked.

The last part of each Buddha carving to be finished was the head. Dozens of stone Buddhas looking like they had cardboard boxes made of stone on their heads sat around as the artisans sculpted the head and faces of other statues. A teenage boy was painting a finished sculpture with bright metallic looking paint.

Shan State

The Shan are the second largest ethnic group in Myanmar after the majority Bamar people. They comprise about 9% of the country’s total population and live mostly in the state named for them. The Shan are very closely related culturally and linguistically to the people of Thailand and Laos. In fact they refer to themselves as Tai. There are a number of different tribes within the Shan ethnic branch.

Large parts of Shan State remain off limits to foreign visitors due to long simmering conflicts against the central government.

My reason for going to Shan State was to go on a hike to some hill tribe villages. I bused from Mandalay to the city of Kyaukme. After getting a hotel room I made arrangements to get a guide to take me on a trek to some Palaung tribe villages in the hills above the town. The guide showed up at my hotel at dawn the next morning. There were 2 other tourists along for the trek. One was a young French man and the other a young woman from Montreal.

We hiked uphill for several hours before reaching the first Palaung village. Being much older than the other 3 I often lagged behind. They didn’t seem to mind but I couldn’t help feeling bad for slowing them down. I was huffing and puffing much of the way. I had thought I was in better shape than I proved to be.

As we entered the first village we saw adults and children bathing at a communal series of water taps all fed by a single pipe. They were all dressed as they soaped up. It was an odd sight. They seemed embarrassed to be seen by us despite being fully clothed.

At the first village we stopped in one of the houses and a Palaung woman made us a very tasty lunch that had been arranged ahead of time. The Palaung houses in that village were made of hardwood and stood on stilts. They appeared to be solidly constructed. I was a little disappointed than none of the tribe were garbed in traditional costumes. Some tribes still wear traditional clothing in Myanmar but I wouldn’t see any that day.

About an hour after we left the first Palaung village we came upon a second one. There we saw three women weaving bamboo panels to be used as walls for huts. I had seen a man in a Chin village in Rakhine State using a a specially designed knife to cut bamboo laterally into very thin long strips for that very purpose.

I was only doing a day trek. My companions on the trek were planning to go to further villages and stay overnight in one of them. My guide phoned a young guy he knew in the village with a motorcycle to come and pick me up and drive me back to Kyaukme. The ride back was on an extremely rough dirt road that was deeply rutted and eroded. It was not a comfortable ride and it took what seemed forever to get back into town. I was bounced up and down more than necessary to cause my lower half to feel semi-paralyzed. It was a good thing that the driver had supplied me with an extra helmet because we kept knocking heads when we hit large potholes. There were a lot of those.

My next destination in Shan State was Kengtung. I wanted to use it as a base for visiting Mong La. Mong La is tucked right up next to the Chinese border. The economy of Mong La is based on catering to the vices of Chinese visitors. Casinos, prostitution, and the trade in wild animal parts are the draw for tourists from Yunnan province in southern China. So dependent is Mong La on business from China that the chief currency used there is the Chinese yuan. All clocks in Mong La are set to Beijing time.

Making the scene in Mong La odder still is the fact that it’s governed by the semi-autonomous Wa tribe who have their very own army, The United Wa State Army, and their own governing political party, the United Wa State Party.

Opium poppies have long been grown in the Wa territory and the sale of opium and its derivative, heroin, were a major source of income for the Wa army and government. More recently methamphetamine production has supplanted opium in importance to the Wa economy. So in short, I was planning to visit a rather sleazy place. I wasn’t interested in involving myself with illegal or unethical activities. I just thought it would be interesting to see a sordid town fueled by vice to see how that reality contrasted with more mundane economic models.

I had to get to Kengtung before I could get to Mong La. The only way the Myanmar government allows foreigners to travel to Kengtung is by air. It was impossible for me to travel there overland. That meant I had to double back to Mandalay and buy an airline ticket there for Kentung. To accomplish that I planned to travel by train.

I had not yet been on one of Myanmar’s antiquated and badly maintained trains. The line between Kyaukme and Mandalay goes over the Gokteik Viaduct. The viaduct is easily Myanmar’s highest bridge. It was built in 1901 and traverses an enormous, and very deep canyon. When trains pass over the viaduct they do so at a crawl. That’s a good thing since our train rocked back and forth a whole lot when it traveled at cruising speed which actually wasn’t very fast. Sitting in my seat I had felt like a bobble head toy perched in the back window of a car. The rocking motion of the car was too pronounced to make reading viable.

I had seen photos taken from the train as it passed over the Gokteik Viaduct and I wanted to get a few of my own. When my train reached near the half way point of the viaduct I stuck my head out the window with my camera in hand and froze with terror when I saw how far down the canyon bottom really was. I hadn’t expected to be so shaken up with fear of heights but I definitely was. Seeing nothing between me and the river far below made my stomach almost jump out of my mouth. Summoning up my courage I tried again. The second time I slowly eased my head and arms out the window. I didn’t hang out far enough to get the shot I really wanted but life is full of compromises I suppose.

On my return to Mandalay I returned to the hotel where I had suffered so grievously from food poisoning. I was lucky enough to get a plane ticket to Kengtung for the next day. By law I also had to fly out of Kengtung when I left there so I bought a one-way ticket from Kengtung to Yangon as well. My trip was winding down and I would have to be in Yangon soon for my return flight home anyway.

After arriving in Kengtung I visited the immigration office in town to apply for a permit to visit Mong La. Turned out that the protocol for doing that had changed considerably. I was informed that to visit Mong La I would have to pay over $300 for a car and driver. I would have to cover all my other expenses on top of that. I knew that Mong La would be more expensive than any other place in Myanmar. My ardour for seeing Sleaze City was blunted by the knowledge that it was going to cost me a whole lot more than I had bargained on. On top of that I had laid out that extra coinage for flights in and out of Kentung already.

I decided to skip Mong La. Kengtung was known as an excellent base for hill tribe trekking and I decided that would be a productive way to use my time there. I arranged through my hotel for a guide to take me to some Akha tribe villages in the hills not far away. I had found hiking in the hills of Shan State to be more arduous than I had originally estimated. I made sure to pay full price for the guide so that I would be his only client. That way I could travel at my own pace and not have to worry about trying to keep up with others. But that was for the next day.

I had read that the market in Kengtung was really worth visiting so I went there and spent several hours looking around. It was crowded with stalls selling goods with only the local people in mind. The Kengtung market certainly was very engaging and I got some good photos there. People from some of the hill tribes were there to buy and sell and many of them were clothed in their traditional garb. The Ahka women were especially interesting to see with their headdresses festooned with coins and metal discs and their black robes. Once again I was amazed at how people in Myanmar don’t mind in the least when some camera-toting tourist starts taking photos. They carry on with what they were doing allowing someone like me to capture images of them acting as if someone like me wasn’t present.

Early the next morning my guide showed up at my hotel right on time. He gave me his business card which I’ve since misplaced. I’m bad with names and can’t remember his. He was with another man driving a car to take us to the trail head. That was an unexpected luxury.

My guide was a likeable man with a jovial personality. He reminded me of Aung, a guide I had hired in Mrauk U. They were of similar age (late 40’s) and build. My hotel had recommended him and he was a good choice. He suggested that we should first go to the market and get take-out lunches for both of us and sweets for tribal people we would meet on our trek. After taking care of business at the market we got back in the car and headed out.

The hike to the Akha villages was uneventful. I was happy to be able to trek at my own pace. It made the whole outing more leisurely and hence more enjoyable. When we arrived at the first Akha village there were only a few women and children around. One woman was decked out in full traditional garb. She had a baby strapped to her back who was also dressed in a traditional fashion. She was happy to let me take a few photos. Small children began gathering around partly because they were curious about me but more so because they expected the guide to be ready to dispense some candy. They weren’t left disappointed.

Soon an old woman showed up and invited us into her hut. She lived alone and her hut was quite ramshackle. She produced a bottle of locally made hooch with a well worn cork stopper and invited us to have a drink. My guide was reluctant to imbibe. I figured the alcohol would have killed any possible problem micro-fauna and took a sip. I was curious to know what Shan moonshine was like. It tasted somewhat like really cheap sake. That made sense to me since I figured it was probably distilled from rice. After all, rice is the leading grain produced in Myanmar like so much of the rest of Asia.

The old Akha woman lived alone. It was interesting to see the inside of her hut. There were large gaps in the bamboo siding of her home. She was obviously very poor. I gave her a little money in gratitude for the hospitality and the sample of moonshine.

After our half day of hiking we went to see some colonial era architecture at a former British hill station. That wasn’t especially enthralling. The buildings were not impressive in any real sense. On the way there we passed a school run by Catholic nuns. Out in the front of the school was a small cage with a monkey inside. I felt bad for the poor animal to be confined in such a small space.

It was early to bed and early to rise for me the next day. Actually that was true of my whole stay in Myanmar. It doesn’t have a late night culture. Even in Yangon and Mandalay the streets were mostly deserted after 9 o’clock in the evening.

I highly recommend Myanmar to anyone who appreciates the experience of spending time in a cultural milieu very different from what we in West countries are accustomed to. With friendly people, savoury cuisine, low prices, and a nascent tourist infrastructure, Myanmar would appeal to anyone curious about what’s on roads less traveled.